Streptococcus Group B - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents

Streptococcus Group B - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial AgentsNo Results

No Results

processing ....

Group B Streptococcus (GBS), also known as Streptococcus agalactiae, are known to cause postpartum infection and as the most common cause of neonatal sepsis. These organisms also cause infections in nonpregnant adults. Group B streptococcal infection in healthy adults is rare, except in young and middle-aged women, and almost always associated with the underlying disorder, diabetes is most often associated with infections in several series.

GBS organism colonizes the vagina, digestive tract and upper respiratory tract of healthy humans. GBS infection is almost always associated with the underlying disorder. In older people aged 70 years or older, GBS infection is strongly associated with congestive heart failure and become bedridden

Signs and symptoms of GBS infection include the following :.

GBS pneumonia: Rare with some unique features; observed in older people with diabetes and neurological deficits; fever, shortness of breath, chest pain, pleuritic pain, or cough

GBS meningitis: a common manifestation of neonatal infection; rare in adults; almost always associated with anatomical abnormalities within walking distance, or, CNS, usually as a result of neurosurgery; fever, headache, neck stiffness, or confusion

GBS bacteremia: General; most cases have no identifiable source of infection; fever, malaise, confusion, chest pain, shortness of breath, myalgia, or arthralgia

Skin and soft tissue infections, decubitus ulcers, colonization infection diabetic foot: Fever, malaise, localized pain, cellulitis < p> osteomyelitis, arthritis, discitis: fever, malaise, localized pain, cellulitis, arthralgia, arthritis, or weakness

Chorioamnionitis, endometritis, UTI (from bacteruria asymptomatic for cystitis and pyelonephritis with bacteremia): fever, dysuria , waist pain, or pelvic pain

Check for more details

examination in patients with GBS infection can show findings as follows :.

consolidation Lung, pleural effusion

Tachypnoea

Tachycardia, murmurs, evidence of heart failure

Hypotension

Pain head, neck stiffness

The confusion, altered mental status, neurologic dysfunction

evidence of an event embolism, phlebitis,

Splenomegali

Vascular insufficiency of the lower limb, wound infection

Back, f skinny, pelvic or abdominal pain

the laboratory tests

Research laboratory in patients with suspected infection of GBS may include the following:

Gram stain

the isolation of GBS from blood, CSF, and / or the site of pus local: the only method for diagnosing infections GBS invasive

GBS antigen detection in blood, CSF, and / or urine

imaging tests

imaging following may be obtained in patients suspected of having an infection GBS:

chest radiography: may showed pneumonia in patients bedridden elderly d ith fever, neurological deficits, or other appropriate symptoms; infiltrate, or effusion can be seen

Radiography of the areas affected in patients who are elderly, sick, or diabetes with fever and symptoms that apply: May revealed evidence of gas or bone destruction in patients with soft tissue infections, osteomyelitis , discitis, epidural abscess, wound infection, necrotizing fasciitis, decubitus ulcers

CT scan of an area affected: May revealed phlegmon, abscess or osteomyelitis

CT scan of the head on neurosurgical patients with fever and other symptoms that apply: May indicate meningitis; may reveal an abscess or infection contiguous

Echocardiography in patients with fever source unclear: May indicate vegetation or evidence of damage to the valve

Ultrasound system GU or pelvis in postpartum women or older men or woman with fever and symptoms that apply: May revealed evidence of obstruction GU or abscesses

CT scan and MRI systems GU or pelvis: May show evidence of obstruction or abscesses

procedure < p> the following is a procedure that can be performed in cases of suspected infection GBS:

Lumbar puncture for suspected GBS meningitis: First, exclude increased intracranial pressure with a CT scan, then perform LP

Diagnostics and therapeutic thoracentesis in GBS pneumonia: in the presence of pleural effusion; empyema require drainage by thoracentesis, chest tube, or surgery

Valve replacement in GBSbacteremia, endocarditis, and line-related sepsis: Because endocarditis damaging

aspiration diagnostic and curative surgery: For GBS soft tissue infections, arthritis, osteomyelitis, discitis and epidural abscesses

diagnostic aspiration / tap with ultrasound or CT scan guidance in UTI or pelvic abscess: to isolate the organism, relieve obstruction, or draining abscesses

Check for more details

Pharmacotherapy <. / P>

infections GBS mainly managed with antibiotics, including the following:

Penicillin G: the drug of choice for infections GBS

Ampicillin: Also the drug of choice for GBS infection

Vancomycin: initial treatment of choice for GBS infection in patients who are allergic to penicillin (because of possible resistance to clindamycin)

clindamycin: Getting sensitivity testing for increased resistance; PO clindamycin remains an excellent agent for parenteral therapy program for bone, soft tissue, and lung infections if the isolates were susceptible

Cefazolin Therapeutic Alternatives to penicillin for GBS infection; ineffective for GBS meningitis

Telavancin: For infections of skin and skin structure complicated caused by gram-positive bacteria susceptible, such as S agalactiae

Gentamicin: synergy potential is when used with penicillin G for GBS

penicillin, ampicillin, or vancomycin remains the preferred treatment for endocarditis.

If the addition of an aminoglycoside to penicillin or ampicillin is being considered to treat GBS infection, it is important to test for sensitivity aminoglycosides, since synergy is not observed if the organism is not sensitive to aminoglycosides. Keep in mind that the group B streptococcal isolates can be resistant to one aminoglycoside and sensitive to others.

Surgery

Although medical therapy should cure the infection much GBS, their skin involves, soft tissue, and bone can not be cured with antibiotics and may require surgical intervention, such as the following:

emergency surgery: Necrotizing fasciitis, septic arthritis, and epidural abscesses

drainage empyema in cases of pneumonia

heart valve replacement in cases of endocarditis, bacteremia and sepsis

Surgery plus parenteral antibiotics for soft tissue infections, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, discitis and epidural abscesses

The intervention to remove the obstruction GU in UTI

Drainage to the pelvis abscesses

See and for more details.

Group B Streptococcus, also known as Streptococcus agalactiae, once regarded as the only domestic animal pathogens, causing mastitis in cows. S agalactiae is now recognized as a cause and as the most common cause of. More recently, various series have been described S agalactiae as cause of infections in nonpregnant adults, provide a description of the clinical spectrum of the disease, including clinical, risk factors, treatment, and outcome of group B streptococcal infections in nonpregnant adults.

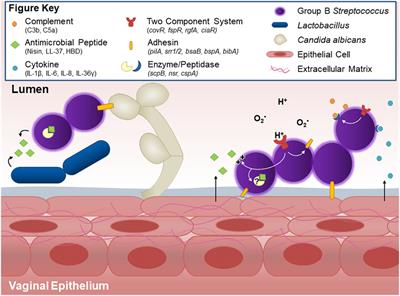

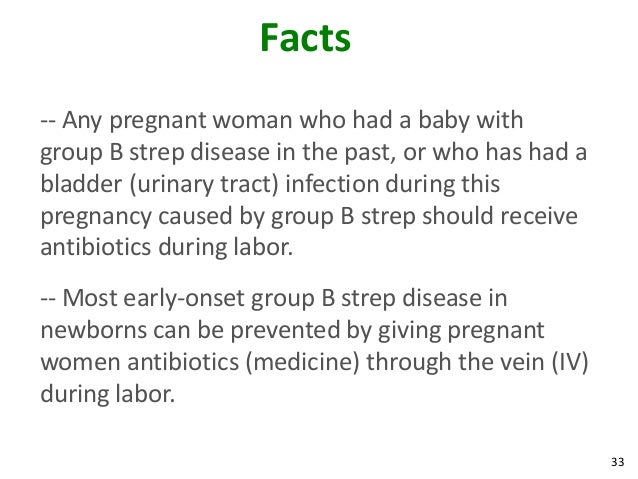

Group B streptococci colonize the vagina and gastrointestinal tract in healthy women, with the train level ranged from 15% -45%. Neonates can obtain vertically organism in the womb or during delivery of maternal genital tract. Although the rate of transmission from mother colonized with S agalactiae for neonates through the vagina is about 50%, only 1-2% of neonates colonized continue to develop invasive group B streptococcal disease. []

Group B streptococcal neonatal sepsis are rare, but more common in the setting of prematurity and prolonged membrane rupture. Because of the ubiquity of S agalactiae colonization in women and scarcity of neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis, prevention of the disease is difficult. Many pregnant women need to be treated to prevent a single neonatal infection. Immunoprophylaxis and chemoprophylaxis both have been studied as a solution to this problem.

neonatal group B streptococcal disease is divided into early and late disease. Early neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis often prize within 24 hours of delivery but can be clear until 7 days postpartum. There are no special features distinguish clinically beginning of group B streptococcal disease caused by other pathogens. Pneumonia with bacteremia is common, while meningitis is less likely.

End group B streptococcal neonatal sepsis is defined as an infection that is a gift between one week and 3 months postpartum, End disease generally involves group B Streptococcus serotypes III, usually marked with bacteremia and meningitis.

The absence of antibodies against group B streptococcus in infants is a risk factor for infection. Due to group B streptococcal antibodies provide protection against disease in animal models, there is ongoing interest in vaccination as an approach to reducing the incidence of group B streptococcal colonization in healthy women. vaccine development never promised, but a shift in group B Streptococcus serotypes responsible for clinical disease limited this approach. Another factor that has made this approach less attractive, including issues relating to access to vaccination by women of childbearing age and possible litigation and emotions associated with vaccination during pregnancy.

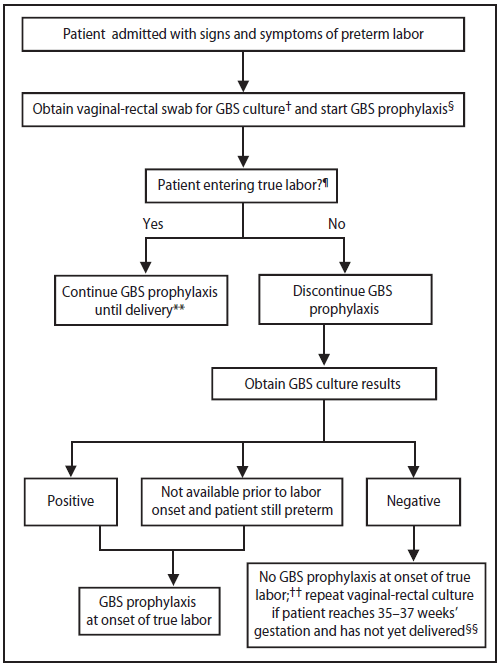

The current approach to the prevention of group B streptococcal infection in pregnancy approach requires intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis in women with evidence-term culture of group B streptococcal infection of the vagina or anus recently. It has become the national standard because of the efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1995. [] Women without status of group B streptococcus is known to give before 37 weeks gestation with premature rupture of membranes or intrapartum fever are also candidates for intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis. Penicillin or ampicillin is the initial approach. Clindamycin and erythromycin standard in individuals with a penicillin allergy, but the group B streptococcus is no longer always sensitive to both drugs.

In just the last 3 decades has the role of group B streptococci as a serious pathogen in nonpregnant adults with well defined. Numerous studies have allowed the description of the clinical spectrum of the disease, including clinical, risk factors, treatment, and outcome.

S agalactiae infection is rare in healthy people and is almost always associated with the underlying disorder. Among the published series, diabetes mellitus and malignancy consistently the most common diseases associated with the underlying infection. [] Other conditions associated with group B streptococcal infection in adults including cardiovascular and genitourinary disorders, neurological deficits, cirrhosis, renal dysfunction ,, steroids, and. Relapse is not uncommon, with approximately 5% of nonpregnant adults eventually develop a second episode of group B streptococcal disease. []

Group B streptococcal infection in the elderly (≥70 y) is strongly associated with and being bedridden, with urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and soft tissue infections as the most common manifestation of infection. neurological disease associated with pneumonia in the elderly, possibly due to aspiration of group B streptococcus from the upper respiratory tract. Group B streptococcal infections are common nosocomial in this group and described in other series. The source of infection is not always clear, but the urogenital tract and the skin is considered a source of nosocomial infections.

Group B streptococci are found commonly in the gastrointestinal tract and has been found to colonize the urethra in men and women without causing an infection. Group B streptococcus can also colonize the upper respiratory tract. Colonization was also observed in the culture of the wound and soft tissue infections clear without. Determining the acquisition and transmission of S agalactiae can be confusing, because it is very invasive but produces little inflammation at the site entries.

Primary group B streptococcal bacteremia without a clear source is a common presentation in adults. While one series showed that group B streptococcal bacteraemia is low grade and easily controlled with a little pain, other authors showed that the clinical presentation may be that classic sepsis with shock and can carry a high mortality. Continuous bacteremia or endocarditis may indicate an infected catheter. Group B Streptococcus can cause endocarditis acute damage, which may require emergency valve replacement.

Urinary tract infections are common manifestations of group B streptococcal disease and observed in pregnant and nonpregnant adults. Another presentation of group B streptococcal infections, including pneumonia, skin and soft tissue, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, and endo-ophthalmitis.

Group B Streptococcus remains sensitive to penicillin and ampicillin and never too sensitive to cefazolin, erythromycin, and clindamycin. Although penicillin is the treatment of choice, it is not clear whether penicillin therapy gives better results than other antibiotics.

S agalactiae is a gram-positive cocci, when grown on sheep blood agar, colonies of gray shimmering white shape with a narrow zone of beta hemolysis. It is packed invasive organisms capable of producing severe disease in immunocompromised hosts. Group B streptococcal infections without concomitant rarely associated medical conditions.

of S agalactiae virulence is associated with toxin polysaccharide yield. Immunity mediated by antibodies to capsular polysaccharide and serotype-specific. Some well-known serotypes Ia, Ib, Ic, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII.

Group B streptococci colonize the vagina, digestive tract and upper respiratory tract of healthy humans. Portal of entry is not clear, but the area may include skin, genital tract, urinary tract, and respiratory tract.

United States

Group B streptococcal neonatal sepsis occurred in 1.8- 3.2 per 1,000 live births. In 2005, early neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis was observed at 0.35 per 1,000 live births, while the end of sepsis was observed at 0.33 per 1000 births. [] The incidence of early disease have declined over the last decade, perhaps because the CDC guidelines for prevention of neonatal colonization with group B streptococcus.

While the incidence of group B streptococcal disease in neonates appears to be decreasing, level in nonpregnant adults appears to be increasing, with an overall increase of 32% between 1999 and 2005. [] A recent study published on the surveillance data from 10 countries found that the incidence of group B streptococcal infection in people aged 15-64 years increased from 3.4 per 100,000 population in 1999 to 5 per 100,000 in 2005. In the adults aged 65 years and older, incidence increased from 21.5 per 100,000 population in 1999 to 26 per 100,000 in 2005. []

International

The role of group B streptococcus in developing countries is not well defined. and serotype carriage rates in women in underdeveloped countries are similar to those observed in the industrial world. However, for reasons unknown, the early group B streptococcal disease in infants is not documented in developing countries.

Group B streptococcal disease results in a significant loss in both neonates and adults. While the death rate ranges from 9-47% in published reports, most studies find that to be about 20%. [] The highest mortality rate in elderly patients with comorbid medical conditions, and most likely to result in death manifestations include endocarditis, meningitis, and pneumonia. The mortality rate is higher in the elderly with group B streptococcal infection may not reflect the organism itself but the conditions or predisposing conditions that place individuals at risk of streptococcus infection group B

neonatal mortality rate of group B streptococcal infection is much less of the adults is not pregnant. Increased awareness of group B streptococcal infection in infants has led to better results in the last few years.

Postpartum group B streptococcal infection is associated with a lower mortality rate for healthy risk group consists of young or middle -aged woman.

Group B streptococcal infections are more common in African Americans than in whites and is much more common in the elderly African Americans than whites older. These differences may be due to differences in socioeconomic rather than racial.

Young and middle-aged women who underwent manipulation of obstetrics and gynecology at increased risk of group B streptococcal infection

Among the non-pregnant patients, group B streptococcal infection has no sex predilection.

The average age for group B streptococcus infection is 64 years.

A bimodal distribution is well recognized. Young and middle-aged healthy women with group B streptococcal infection secondary to manipulation in obstetrics or gynecology is one group, while the second group are parents with group B streptococcal infection as a complication of preexisting diseases.

Nandyal RR. Update on the group B streptococcal infection: perinatal and neonatal periods. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. July-September 2008 22 (3): 230-7. ,

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: a public health perspective. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. , Recomm Rep MMWR 1996 May 31, 45: 1-24. ,

PY Huang, Lee MH, Yang CC, Leu HS. Group B streptococcal bacteremia in adults who are not pregnant. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006 June 39 (3) :. 237-41. ,

Sendi P, Johansson L, group-Teglund A. Invasive Norrby B streptococcal disease in adults who are not pregnant: a review with emphasis on skin and soft tissue infections. Infection. 2008 March 36 (2): 100-11. ,

CR Phares, Lynfield R, Farley MM, Mohle-Boetani J, Harrison LH, Petit S, et al. Epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1999-2005. JAMA. 7. May 2008 299 (17): 2056-65. ,

Gardam MA, Low DE, Saginur R. Group B streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998. 158: 1704-8. ,

Daniels J, Gray J, Pattison H, T Roberts, Edwards E, Milner P, et al. rapid test for group B streptococcus during labor: a study by the evaluation acceptance test accuracy and cost effectiveness. Health Technol Assess. 2009 September 13 (42): 1-154, iii-iv. ,

Lin TA, Weisman LE, Azimi P, Young AE, Chang K, Cielo M, et al. Rate intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for Prevention of Early-onset Group B Streptococcal Disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011 September 30 (9): 759-763. , ,

Schwope OI, Chen KT, I Mehta, Re M, Rand L. Effect of chlorhexidine-based surgical lubricant during a pelvic examination on the detection of group B Streptococcus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. March 2010 202 (3): 276.e1-3. ,

Wu HM, Janapatla RP, Ho YR, KH Hung, CW Wu, Yan JJ, et al. The emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in group B streptococcal isolates in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. May 2008. 52 (5): 1888-1890. ,

Bayer AS, Chow AW, Anthony BF. serious infections in adults due to group B streptococci. Clinical and serotypic characterization. Am J Med. 1976. 61: 498-503. ,

Berardi A, Rossi C, Lugli L, Creti R, Bacchi Reggiani ML, et al. Group B streptococcus late-onset disease: 2003-2010. Pediatrics. February 2013 131 (2): e361-8. ,

Colford JM Jr, Mohle-Boetani J, Vosti KL. Group B streptococcal bacteremia in adults. Five years of experience and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995 July 74 (4) :. 176-90. ,

Dworzack DL, Hodges GR, Barnes WG. Group B streptococcal infection in adult males. Am J Med Sci. 1979. 277: 67-73. ,

Farley MM, RC Harvey, T. Stull population-based assessment An invasive disease due to group B Streptococcus in nonpregnant adults. N Engl J Med. 1993. 328: 1807-1811. ,

Gallagher PG, Watanakunakorn C. Group B streptococcal bacteremia in public teaching hospitals. Am J Med. 1985 May. 78 (5): 795-800. ,

Harrison LH, Ali A, Dwyer DM. Recurrence of invasive group B streptococcal infection in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1995. 123: 421-7. ,

Jackson LA, Hilsdon R, Farley MM. The risk factors for group B streptococcal disease in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1995. 123: 415-20. ,

Lerner PI. Meningitis caused by Streptococcus in adults. J Infect Dis. 1975. 131 Suppl: S9-16. ,

Lerner PI, KV Gopalakrishna, Wolinsky E. Group B streptococcus (S. agalactiae) bacteremia in adults: analysis of 32 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977. 56: 457-73. ,

Opal SM, A Cross, M. Palmer Group B streptococcal sepsis in adults and infants. Contrast and comparison. Arch Intern Med. 1988. 148: 641-5. ,

Persson E, Berg S, Bergseng H, K Bergh, Valsö-Lyng R, Trollfors B. antimicrobial susceptibility of invasive group B streptococcal isolates from the south-west Sweden 1988-2001. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008. 40 (4): 308-13. ,

Pullen LC. Mom probably the main source of LOD Strep in the neonate. Medscape Medical News. January 7, 2013. Available at. Accessed:. March 4, 2013

Schuchat A. Group B streptococcus. Lancet. 1999 Jan 2. That 353 (9146): 51-6. ,

Schwartz B, Schuchat A, Oxtoby MJ. Invasive group B streptococcal disease in adults. A population-based study in metropolitan Atlanta. JAMA. 1991. 266: 1112-4. ,

Trivalle C, Martin E, P. Martel Group B streptococcal bacteremia in the elderly. J Med Microbiol. 1998. 47: 649-52. ,

Verghese A, Mireault K, Arbeit RD.Group B streptococcal bacteremia in men. Rev Infect Dis. 1986. 8: 912-7. ,

Eden PR, Herring CF-3. Group B streptococcus test. MLO Med Lab Obs. 2015 July 47 (7) :. 52..

[Manual] Prevention of Early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease: Green-top Guideline No. 36. BJOG. 2017 September 13 ..

RCOG V. Hackethal Suggest GBS prophylaxis in premature Labor Women. Medscape News. Available in . September 20, 2017; Accessed:. October 12, 2017

Christian J Woods, MD, Program Director of the Association of FCCP for Internal Medicine, Program Director Associate Pulmonary / Critical Care, MICU Associate Director, present at the Infectious Diseases / Pulmonary / Critical Care, MedStar Washington Hospital Center Christian J Woods, MD, FCCP is a member of the following medical societies: ,,,,, Disclosure: Serve (d) as a speaker or a member of the speakers bureau for :. Cubist Pharmaceuticals

Charles S Levy, MD Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, the George Washington University School of Medicine Charles S Levy, MD is a member of the following medical societies: ,, Disclosure: Nothing to disclose

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD, Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy ;. Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug ReferenceDisclosure: Received salary of Medscape to work. for:. Medscape

John L Brusch, MD, FACP Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Consulting Staff, Department of Medicine and Infectious Diseases Service, Cambridge Health Alliance John L Brusch, MD, FACP is a member of the medical community follows :, Disclosure :. Nothing reveals

Michael Stuart Bronze, MD David Ross Boyd Professor and Chairman, Department of Medicine, Stewart G Wolves Endowed chair in internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; Master of the American College of Physicians; Fellow, Infectious Diseases Society of America; Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, London Michael Stuart Bronze, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Disclosure ,,,,,, :. Nothing reveals

Pranatharthi Haran Chandrasekar, MBBS, MD Professor, Chief of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal medicine, Wayne State University School of Medicine Haran Pranatharthi Chandrasekar, MBBS, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Disclosure ,,, :. Nothing reveals

The author and editor of Medscape Reference grateful for the contributions of the co-authors before Mohamad Ossiani, MD, for the development and writing of this article.

Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease

Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease Streptococcus Group B - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents

Streptococcus Group B - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents Group B Streptococcal Infections | American Academy of Pediatrics

Group B Streptococcal Infections | American Academy of Pediatrics CDC Updates Guidelines for the Prevention of Perinatal GBS Disease ...

CDC Updates Guidelines for the Prevention of Perinatal GBS Disease ... CDC Updates Guidelines for the Prevention of Perinatal GBS Disease ...

CDC Updates Guidelines for the Prevention of Perinatal GBS Disease ... Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of group B Streptococcus ...

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of group B Streptococcus ... Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease

Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease Streptococcus Group B - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents

Streptococcus Group B - Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents CDC Updates Guidelines for the Prevention of Perinatal GBS Disease ...

CDC Updates Guidelines for the Prevention of Perinatal GBS Disease ... GBS Testing - Group B Strep International

GBS Testing - Group B Strep International GBS | Prevention in Newborns | Group B Strep | CDC

GBS | Prevention in Newborns | Group B Strep | CDC Antibiotic susceptibility patterns and prevalence of group B ...

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns and prevalence of group B ... Sebastian's Story - Group B Strep International

Sebastian's Story - Group B Strep International Recommendations for the Prevention of Perinatal Group B ...

Recommendations for the Prevention of Perinatal Group B ... Group B Strep Protocol

Group B Strep Protocol Group B Strep (GBS) During Pregnancy: Risks to the Baby

Group B Strep (GBS) During Pregnancy: Risks to the Baby Specific Bacterial Infections: Group B Streptococcus | GLOWM

Specific Bacterial Infections: Group B Streptococcus | GLOWM CDC Updates Guidelines for Prevention of Perinatal Group B ...

CDC Updates Guidelines for Prevention of Perinatal Group B ... Group B streptococcal carriage, antimicrobial susceptibility, and ...

Group B streptococcal carriage, antimicrobial susceptibility, and ... Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease

Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease New group B strep guidelines clarify management of key groups ...

New group B strep guidelines clarify management of key groups ... Prevention of Group B Streptococcal Disease in the Newborn ...

Prevention of Group B Streptococcal Disease in the Newborn ... Do Patients with Strep Throat Need to Be Treated with Antibiotics ...

Do Patients with Strep Throat Need to Be Treated with Antibiotics ... Epidemiology of Group B Streptococcal Disease in the United States ...

Epidemiology of Group B Streptococcal Disease in the United States ... Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease: A Public ...

Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease: A Public ... Group B Strep Treatment: What to Do If You Test Positive for GBS

Group B Strep Treatment: What to Do If You Test Positive for GBS GBS is treated with IV antibiotics... - Group B Strep ...

GBS is treated with IV antibiotics... - Group B Strep ... Specific Bacterial Infections: Group B Streptococcus | GLOWM

Specific Bacterial Infections: Group B Streptococcus | GLOWM Frontiers | Group B Streptococcal Maternal Colonization and ...

Frontiers | Group B Streptococcal Maternal Colonization and ... Group B Strep, A Danger to Infants: GBS Awareness Month | Sepsis ...

Group B Strep, A Danger to Infants: GBS Awareness Month | Sepsis ... Group B Strep and Yogurt Squatting - preg U

Group B Strep and Yogurt Squatting - preg U Group B strep

Group B strep Group B streptococcal infection - Wikipedia

Group B streptococcal infection - Wikipedia How to Get Rid of Group Beta Streptococcus (GBS) | Wellness Mama

How to Get Rid of Group Beta Streptococcus (GBS) | Wellness Mama Intrapartum antibiotics for GBS prophylaxis | Download Table

Intrapartum antibiotics for GBS prophylaxis | Download Table Prevention of Neonatal Group B Streptococcal Infection - American ...

Prevention of Neonatal Group B Streptococcal Infection - American ... Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease

Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease WHO recommendation on intrapartum antibiotic administration to ...

WHO recommendation on intrapartum antibiotic administration to ... Streptococcus agalactiae (group B strep)- causes, symptoms ...

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B strep)- causes, symptoms ... Fit For You: Prenatal Probiotics Research | WUWM

Fit For You: Prenatal Probiotics Research | WUWM Modelling the effect of the introduction of antenatal screening ...

Modelling the effect of the introduction of antenatal screening ... Group B Streptococcus | Sepsis Alliance

Group B Streptococcus | Sepsis Alliance Risk factors for group B Strep infection in babies poster by Group ...

Risk factors for group B Strep infection in babies poster by Group ... Evidence on Group B Strep in Pregnancy

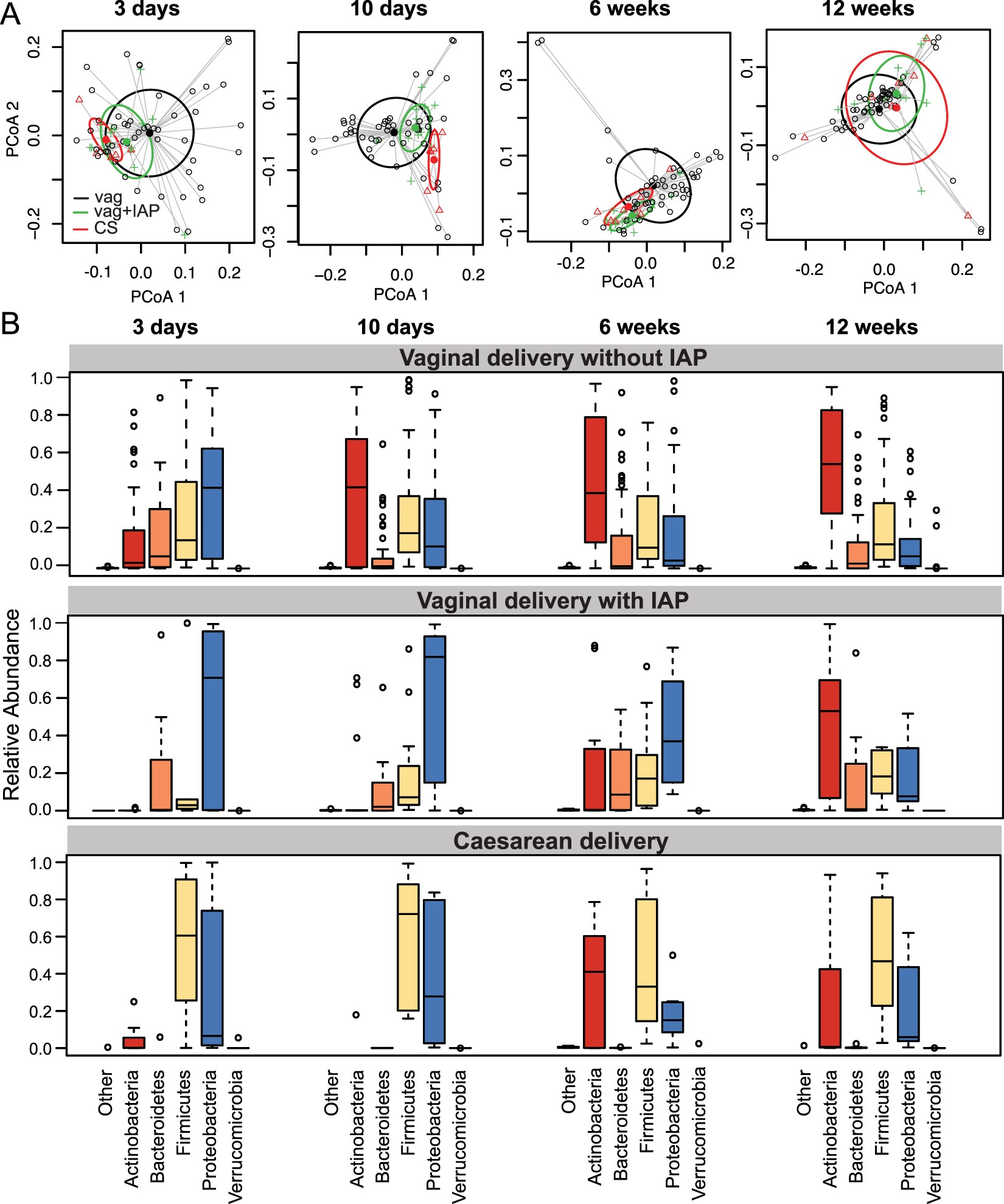

Evidence on Group B Strep in Pregnancy Intrapartum antibiotics for GBS prophylaxis alter colonization ...

Intrapartum antibiotics for GBS prophylaxis alter colonization ... Pin on Group B strep

Pin on Group B strep Epidemiology of Group B Streptococcal Disease in the United States ...

Epidemiology of Group B Streptococcal Disease in the United States ... Group B Strep: Yes or No? - Healthy Home Economist

Group B Strep: Yes or No? - Healthy Home Economist Group B strep

Group B strep Real Life Stories on Group B Strep - Evidence Based Birth®

Real Life Stories on Group B Strep - Evidence Based Birth® Group B Strep Treatment, Symptoms, Infection During Pregnancy

Group B Strep Treatment, Symptoms, Infection During Pregnancy

Posting Komentar

Posting Komentar